Researching history for Deaf Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future

- Hannah Salisbury, Deaf Perspectives Project Co-ordinator

One of the aims of the Deaf Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future project was to investigate Suffolk’s deaf history stories. Some of these appear in the short films made by the project, and a selection are presented here in more detail.

The research includes several stories of deaf individuals and families who we have traced through historical records, including newspapers. Newspapers can provide insights into people’s lives that cannot be easily found elsewhere, but they tend to report the unusual and the tragic rather than the everyday. This means that the stories we have found tend to highlight unusual negatives, rather than the ordinary daily life, friendships, and achievements that will have made up many people’s experiences.

A Question Forms...

Walton Burrell – The World Traveller

In November 1944 an extraordinary man named Walton Burrell died in Bury St Edmunds. His obituary in a local newspaper was headed ‘World Traveller’s Death’. For Walton had indeed travelled the world extensively, from Australia to Egypt to Hawaii and many other places – a very unusual accomplishment for someone of his time. He had taught himself several languages, and travelled independently, making new friends as he went.

He must have been a master of communication, especially given the fact that he was profoundly deaf from birth and did not speak. The only direct evidence we have of how Walton communicated comes from an interview with a local journalist about his 1931 trip to Australia, which tells us that he used a mixture of lip reading, writing notes, and gesture to communicate with hearing people.

Walton Burrell and Spot the dog (K997/127/9, courtesy of Suffolk Archives / the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Walton Burrell’s Early Life & Legacy

Open each section below to explore how Walton’s life, photography, and privilege connect to wider questions about deaf history.

Early Life & Family

Walton was born in 1863, one of 12 children who would survive to adulthood. 3 of his siblings were also born deaf, and all attended a private school for deaf children in London. Given this, Walton may have used some ‘home signs’ with his siblings and fellow pupils – spontaneously generated signs, possibly augmented with fingerspelling. We can only speculate.

Learning the Art of Photography

As a young man Walton learnt the complicated art of photography, and took thousands of photos over several decades. His pictures include the home and social life of family and friends, and extensive photography of the home front in West Suffolk during the First World War.

You can find out more about Walton in this online display.

Walton and his photographs were the inspiration for

a project with deaf children and young people in Bury St Edmunds in 2022-3

,

which resulted in a concert of music inspired by his photos.

Questions form

While exploring his story, one question came up repeatedly: how did he afford all of his travel? Why did he not need to get a job to earn a living? The answer is a simple one – he was from a wealthy family, and simply did not need to work to earn money.

Another question naturally followed. What was life like for other deaf people at the time who did not have the kind of financial resources which Walton did? And how could we find out? This was the question which began the historical research which helped to shape some of the Deaf Perspectives films.

Looking for Answers

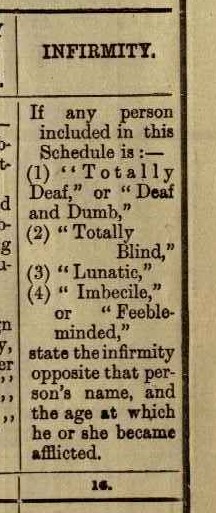

The one place (almost) everyone who lived in England at the same time as Walton Burrell will be recorded is in the Censuses that were taken every 10 years starting in 1841. These record the name, age address, occupation, and birthplace of all people living in England and Wales. The exact data they collected varied a bit overtime, and the 1911 Census is the best one to look in for data on deafness.

For the 1911 Census every household was sent a form to fill out about the people who lived there. The final column of the form is headed ‘Infirmity’, and asks for information about deafness, blindness, learning disabilities, and mental health. The language used is of its time, and would be considered offensive today.

Census records up to 1921 are now digitised and can be searched online.

On the Find My Past website, you can search by area (e.g. Suffolk)

and then filter by a keyword such as “deaf”.

1911 Census record for the Binks family of Haverhill

Investigating the Records

When I first tried this search I expected to find a few dozen results, but actually there were nearly 600. I was going to need some help investigating them all.

Fortunately 5 volunteers – Rachel, Steve, Tessa, Helen, and Allan – came forward to help with the task, and one by one we entered each person into a database. The result is a database of 578 deaf people who were recorded in Suffolk in 1911. With all this information gathered together, we could look for patterns, and identify interesting-looking individual stories to research further.

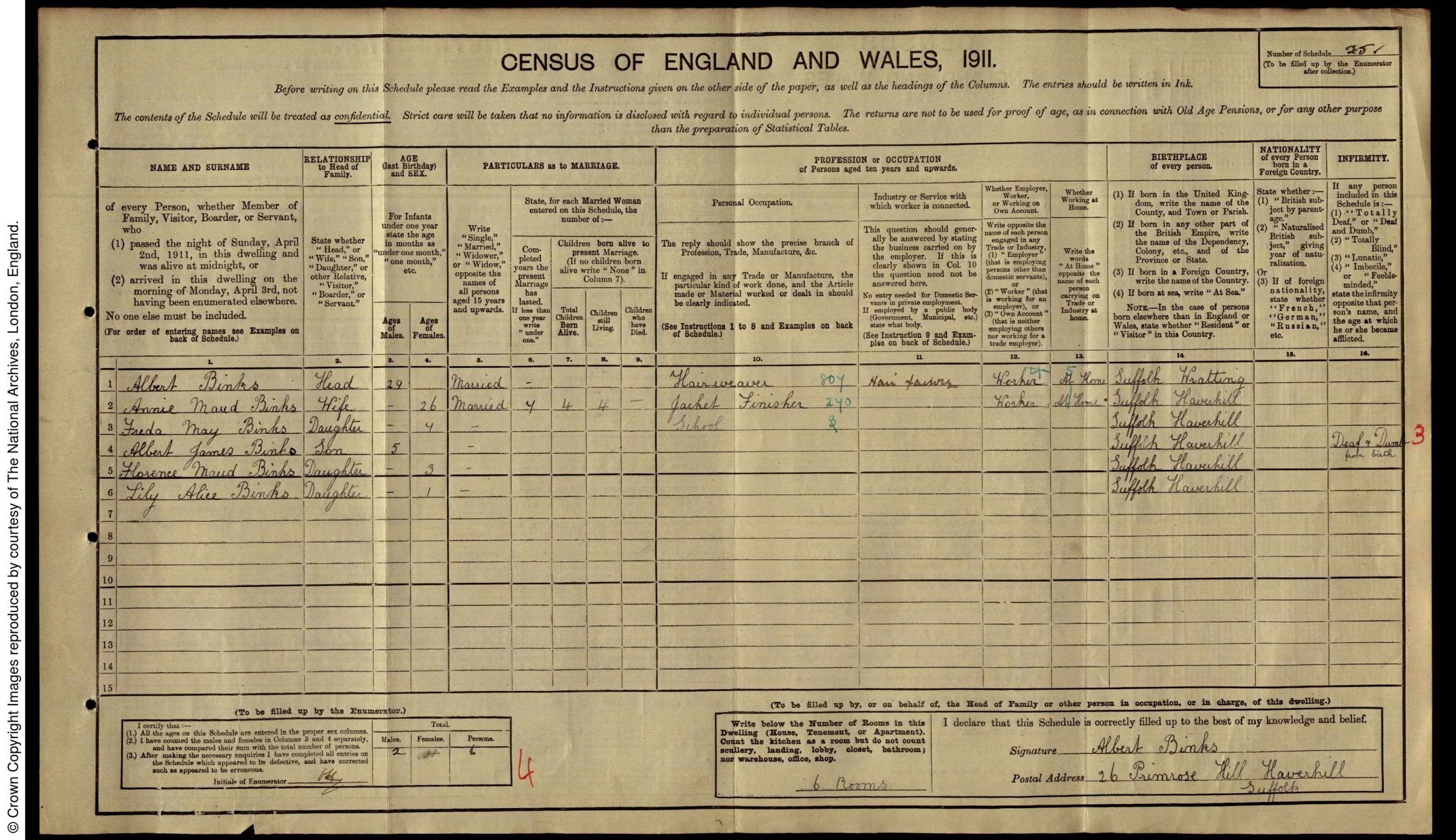

When did people become deaf?

One of the things we have looked at is the age at which people become deaf. Many records provide plenty of detail on this – e.g. ‘Deaf from birth’, or ‘deaf from the age of 20’, but others do not. We have drawn on other records to fill in as many blanks as possible, and the figures presented here are the result of that work.

48% of the 580 people we have information for were deaf from birth, childhood, or their teenage years. For some of these their deafness would have been hereditary, and for others it would have been the result of common childhood illnesses such as scarlet fever or measles.

Pie chart showing the age at which people in our database became deaf

Youngest and Oldest People Found

The youngest people we found were 2 years old:

- Frank Hawes of Palgrave, the youngest of 8 children, and the only deaf member of his family.

- Sidney Ernest Barber of Ilketshall St Margaret, the youngest of 9 children and the only deaf member of his family

- Thomas Phillips, the son of a Lowestoft fisherman, and again the only deaf member.

The oldest person in the database is Catharine Childs, a 97 year-old patient at Newmarket Hospital who had become deaf in later life.

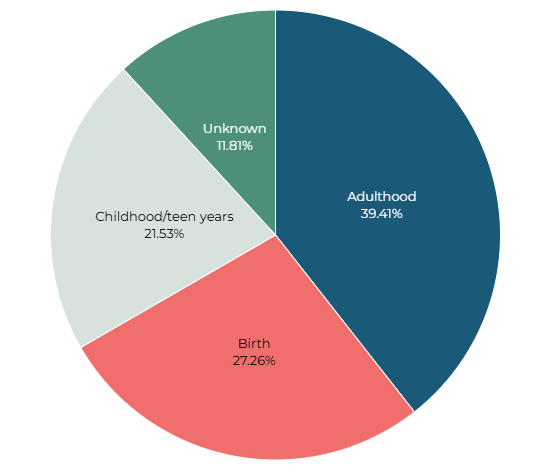

What were educational opportunities like?

There were no schools for deaf pupils in Suffolk in 1911. If parents wanted their deaf children to access specialist education, they would have to send them to a boarding school. This would likely mean improved access to education for their children, but also that their child would be away from home for long periods.

Alongside their academic lessons, students learnt vocational skills such as dressmaking, carpentry, and, as shown in this photograph, boot making at the Royal School for the Deaf in Margate.

Image courtesy of Kent Archives, Ch1921/A2/68.

For those who could afford it, there were a number of private, fee-paying schools for deaf children. For the majority of parents who could not afford this, they might have the opportunity to send their children to one of the charitable schools for deaf pupils, in London, Margate, Edgbaston, or Brighton. Demand for places at these schools outstripped supply, so not everyone who applied secured a place. However, several of the people in our database did attend one of these charitable schools.

The first school for the deaf in Britain was founded by Thomas Braidwood in Edinburgh in 1760. Braidwood was hearing, and learnt signs from his pupils. His methods combined sign language and the study of articulation and lip reading. In 1783 he moved his school to Hackney. The school was fee-paying, and Braidwood kept his methods secret. The school is widely considered to have been very successful in teaching its students.

The period of 1792-1860s is described by many as a golden age for sign language in deaf education. In the later part of this period, tension was growing between those using the combined system like Braidwood (using both speech and sign) and those who advocated oralism, that is, teaching only speaking and lip reading, who thought that sign language was inferior to spoken language.

In the mid-late nineteenth century oralism gained momentum across Europe, and the views of deaf people were increasingly ignored. An international conference on deaf education was held in Milan in 1880. Most of the presentations promoted oralism, and the view that signing was harmful to the development of speech. No deaf person addressed the conference (only one deaf person was present). 160 delegates voted for oralism, and 4 against. Speech had been deemed superior to signing. Later research showed that claims about the advantages of an oral system could not be substantiated. Often the deaf children who were presented to the public as ‘oral successes’ were those who were born hearing and became deaf after having had some exposure to hearing and learning speech.

A speech class at the Royal School for the Deaf in Margate.

Image courtesy of Kent Archives, Ch1921/A2/68

Following the Milan conference, in the UK a Royal Commission was set up which recommended using speech in the teaching of deaf children. No deaf people were involved in this commission either. From this point, teachers of the deaf in the UK were trained in strict oralism, even being taught not to use natural gestures while talking. As a result, many deaf teachers of the deaf lost their jobs.

We have so far identified 66 Suffolk people in our 1911 Census data who had attended one of the deaf boarding schools. They make up 23% of the 281 people in the records who were deaf before the age of 18. This is almost certainly an underestimate as it has not been possible to investigate all the relevant records.

Of the 66 people who we know went to a deaf school, 33 were male and 33 female. The vast majority (42) went to the Royal School for Deaf Children in Margate, which was the geographically closest to Suffolk, with small numbers going to schools in Edgbaston, Brighton, and elsewhere.

The opportunity to attend one of these schools could be spread unequally within families. The Last family of Ipswich, for example, had three hearing children and three deaf children. The oldest deaf child, Frances, did not leave Ipswich, and must have had to make-do with whatever schooling would have been available locally. Her two younger sisters, however, both went to the specialist school for deaf children in Margate. Frances followed in her mother’s footsteps as a dressmaker and never left home. Her younger sisters both moved out and married, one of them to a deaf man. It could be that attending school broadened someone’s horizons and gave them more opportunities in life.

Admission to the specialist schools was by a voting system. This notice asking for votes for Alice Last

appeared in the East Anglian Daily Times.

Image courtesy of the East Anglian Daily Times.

Teaching in the 20th Century

In the 20th century teaching of deaf children was highly focused on teaching speech. Methods even included teachers putting their fingers in children's mouths.

Signing was not allowed, and children caught signing could face severe punishment, including being strapped into garments which pinned down their arms. The emphasis was on learning to speak, not learning knowledge. Some former pupils of deaf schools in the mid-20th century describe being taught to parrot speech without understanding what they were saying.

It has been contended by many that this period did huge amounts of damage to deaf children. It is only in quite recent years that sign language has started to re-emerge in deaf education.

What sort of jobs did deaf people do in 1911?

We have a broad range of occupations represented in the database. Given that the majority of our people are over 60, it is unsurprising that the biggest category we see here is people who were retired, many of them drawing the brand new Old Age Pension.

Of those who were in work, we have:

- Lots of people working as labourers in agriculture or industry

- A painter

- An architect

- Several tailors or dressmakers

- Several shoemakers

- Many people in domestic work, both inside and outside of their own home

- A teacher

- A shepherd

- Mat makers

- Servants

- Several Laundresses

- Several gardeners

- A brewery cooper

- A bookbinder

- A golf caddy

- Any many more in other fields of work.

The two major factors which seem to influence people’s occupations are where they were born/lived, and the socioeconomic status of the family they were born into, with many people following their parents into occupations.

Women at work in a factory. Deaf people in 1911 seem to have often done the same jobs as their hearing relatives

and neighbours in local industries.

Image courtesy of Sudbury Photo Archive.

Understanding the Occupation Patterns

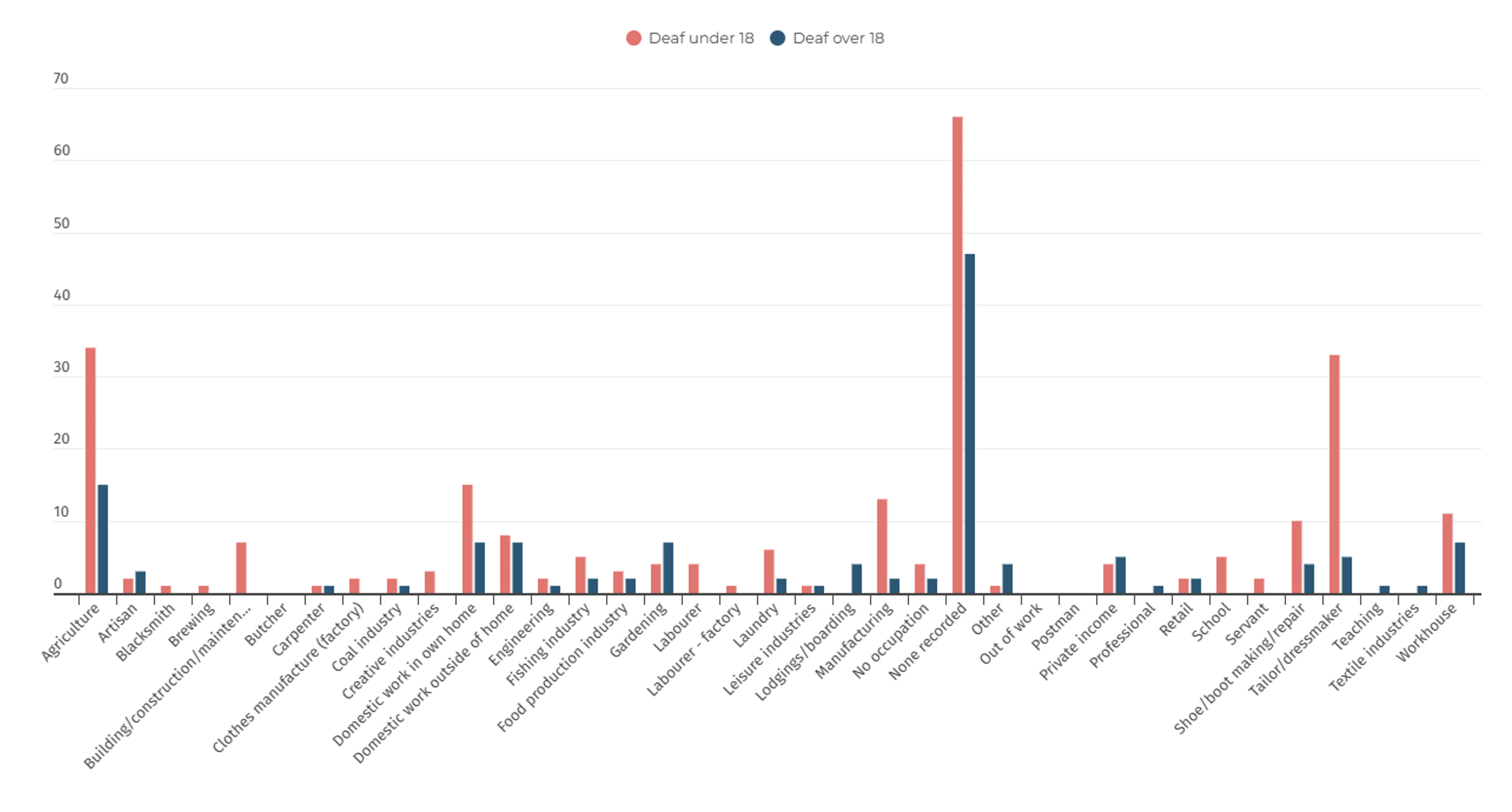

The graph below shows the different occupations of the people in the database, with the pink columns representing people who were deaf before the age of 18, and the blue columns representing those who became deaf after the age of 18. Those deaf before the age of 18 are over-represented in occupations that would likely have paid less, such as labouring. They are also more likely to be working as tailors, dressmakers, and shoe makers, perhaps because these occupations were taught in the deaf schools.

Those deaf before the age of 18 are over-represented in occupations that likely paid less, such as labouring. They are also more likely to be working as tailors, dressmakers, and shoemakers — perhaps because these skills were taught in the deaf schools.

Data graph from the Deaf Perspectives research

A Rare Professional Career

One noticeable thing is that we have only found one deaf person in a ‘professional’ occupation – James Butterworth, who was an architect. James was born in about 1831 in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire. In the 1911 Census he described himself as being deaf since the age of 20.

This is the only mention in any record of his deafness, so perhaps he was partially deaf rather than totally deaf, but we can only speculate.

He began his working life as a builder’s clerk but by the 1860s was living and working in Ipswich as an architect and surveyor. He had a long career in Ipswich, working on domestic projects and also public buildings such as schools and churches.

Were deaf people more likely than hearing people to end up in the workhouse?

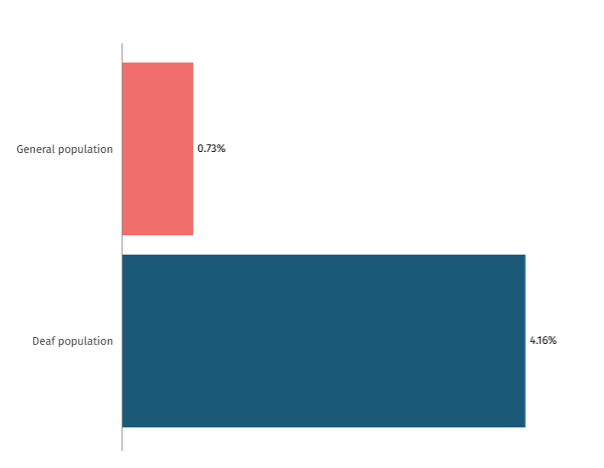

The information we have suggests that deaf people were more likely than average to end up in a workhouse, particularly those who were deaf from birth or childhood. 24 of the people in our database were living in workhouses, 19 as inmates, 5 as patients. About 0.7% of the general population of Suffolk were in the workhouse in 1911, but for deaf people the figure was over 4%. Over half of these people were deaf before the age of 18, and most were unmarried.

Comparison Chart

Long-Term Workhouse Residents

At least 7 people were inmates for at least ten years. Sarah Ann Crick, born deaf in 1835 in Thorpe Morieux, was an inmate of Cosford Workhouse for over 30 years. The longest-term workhouse resident we have found was Frederick Clarke. He was living in Plomesgate union workhouse in Wickham Market in 1891 aged 5, and was still there in 1901, 1911, and 1921. By 1921 he was aged 35 and was a general labourer for the Plomesgate Board of Guardians. The only education Frederick seems to have received was 2 years at the Royal School for the Deaf in Edgbaston between the ages of 13 and 15 – well past the age where language can be learned easily. What happened to Frederick after 1921 is a mystery. Plomesgate workhouse closed in 1936; if he was still alive then it must have been very difficult for him to leave the institution where he had spent his entire like.

Communication challenges?

Robert Prettyman, born deaf in Lowestoft in 1883, had a difficult time as a young man. He had spent some time at the deaf school in Edgbaston in his teens, and a newspaper snippet tells us he could read but not write. (Learning the skill of writing in his teens would have been extremely difficult if he had been deprived of language and education in earlier childhood.)

Robert pops up a few times in local newspapers for minor run-ins with the law. In 1902 he was charged with assaulting a parkkeeper in Lowestoft. A short newspaper report on court proceedings tells us ‘the state of the boy’s mind had been enquired into, and he had been sent to an asylum’. It’s impossible to know whether Robert was experiencing mental health issues, or whether the whole incident occurred because of communication barriers.

In 1903 he was in trouble again for throwing stones at William Day, a fish worker. His mother was in court and said ‘her son was no trouble to her. He got a job now and again’. Robert had a co-defendant, Frederick Rackham, who was also involved in the assault on William Day. Rackham and Day had argued the previous week, which had prompted the assault Robert was involved with.

The next time we hear of Robert in the papers is in 1912 when he was charged with assaulting a man at Kirkley football ground:

‘Complainant said he was on the stand at Kirkley, watching a football match, when defendant held up his fingers to indicate the score at the moment. Witness held up his fingers to indicate his opinion of the final score, whereupon defendant took a ring from his pocket – a “knuckleduster” – which he put upon his finger and suddenly attacked him, blackening his eyes and making his nose bleed profusely.’

Robert’s mother was in court interpreting for him, and said that the ‘complainant’s putting up two fingers conveyed a bad insult to the defendant.’ Robert pleaded guilty and was fined 1 shilling.

One interpretation of all this could be that Robert was quite vulnerable and communication barriers could well have been a factor in the disagreements he found himself embroiled in.

Did being deaf affect whether people got married?

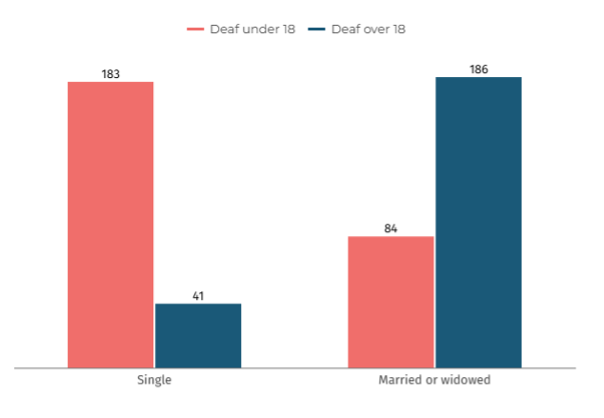

The data we have collected shows that people who were deaf from early life were much less likely to get married than hearing people.

There are 266 people in our database who were over 18 when the 1911 Census was taken, and were deaf from birth, childhood, or their teen years. Of these, 182 were unmarried, and 84 were married or widowed. Of those who were married, most were married to hearing people.

In contrast, of the 227 people who became deaf in later life, only 41 were single and 186 were married or widowed.

Graph showing the number of people in our database who were single or married/widowed,

and whether they were deaf before or after the age of 18.

This graph shows the striking difference in marriage rates between people who were deaf before the age of 18, and those who became deaf after the age of 18. Those who became deaf after the age of 18 were much more likely to get married than those who were deaf from earlier in life.

There is also a difference in the age at which people married depending on whether they became deaf before or after the age of 18, with those who were deaf from early life tending to marry later. Those deaf after the age of 18 have an average marriage age of 27.1 years. Those deaf before the age of 18 have an average marriage age of 29.3.

There are probably several factors at play here. Of course, some of these people may have simply had no wish to marry. Others may have wanted to marry but faced barriers of communication and decreased opportunities for education, employment, and socializing.

Historically there has also been stigma around deaf people marrying. This was driven partly by the mistaken view that deaf people were not intellectually capable of consenting to marriage, and partly by prejudice against deaf people marrying and producing deaf children.

The challenge of meeting people, particularly for deaf people in rural areas, is possibly what led to the late marriage of Boaz Hart of Woodbridge and Fanny Aggis of Chelmondiston. Both were deaf from birth, and married in 1938 aged 54 and 48, six months after meeting at a deaf social event.

Health outcomes and family stories

Click each heading below to expand and read the full story.

Health outcomes – Frederick Hadfield

In 1911, just as now, deaf people sometimes experienced poorer health outcomes. Frederick Hadfield, who became deaf aged 6 due to scarlet fever, had a long career as an engineer with the Great Eastern Railway. He seems to have retired aged about 40, and settled in the tiny village of Ringsfield near Beccles in about 1901. Despite retirement, Frederick kept up his membership of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and even took out a Patent in 1911.

Frederick’s last home was a three bedroom house in Oulton Broad with two acres of garden and a frontage onto the river. Despite his materially comfortable circumstances, Frederick had a very sad end to his life. He fell ill over Christmas 1933 but could not summon any help. Eventually the Police broke into his house, found him starving, and took him to Lowestoft Hospital where he died on 3 January 1934.

CODAs – Robert and Elizabeth Last

As already mentioned, marriages in which both parties were deaf were relatively rare, but we do have a few examples. Robert and Elizabeth Last were one such couple.

Robert Last was born in Ipswich in 1875. He was deaf from birth. His parents were publicans, and he grew up in a series of pubs they managed in the town, including the Station Hotel.

In 1901 he married Elizabeth Bailey, who was also deaf from birth. She was in her late 20s and a widow who had also lost a child. Robert and Elizabeth had two children together, Lily and Daniel, who were both hearing.

Robert and Elizabeth had a bumpy time with their daughter Lily when she was in her early teens. In 1915-16 Robert was called several time to Ipswich Police Court over Lily’s non-attendance of school. They lived at the time at 9 Shafto Terrace on Bramford Road, and Lily was required to attend Bramford Road School. Robert was fined several times over Lily’s lack of school attendance.

In September 1915 an Evening Star report tells us a little more. Robert was ‘summoned for habitually neglecting the education of his child. Mr George Billam, Secretary to the Education Committee, said that … The parents were both deaf and dumb and the girl took advantage of her parents’ affliction. The Committee felt it was no use proceeding further under the by-laws and that it would be best for the girl to be sent to an industrial school’.

Industrial schools were institutions for children and teenagers who found themselves in legal trouble. In July 1916 Lily was sent to King Edward Industrial School for Girls in Hackney. It’s not possible from these records to understand why Lily was not attending school, or to know how she or her parents felt about her committal to an industrial school far from home.

A few years later, aged 17 or 18 Lily had a child outside of marriage – something which was strongly disapproved of at the time. However, her parents stuck by her, and in 1921 she was living with them with her baby daughter.

CODAs – Thomas William Ward

Another deaf parent among our records is Thomas William Ward from Aldeburgh. Thomas was born in the coastal village in 1842, the son of a fisherman. He was one of several children, three of whom were born deaf. Aged 29 Thomas married Catherine Lewis, who was hearing. Thomas was working as a tailor and Catherine as his assistant. The couple went on to have at least 10 children together who all seem to have been hearing.

Aged 29, Thomas married Catherine Lewis, who was hearing. Thomas was working as a tailor and Catherine as his assistant. The couple went on to have at least 10 children together, who all seem to have been hearing.

CODAs – John Henry Booty

Another of the many tailors in our records is John Henry Booty of Walsham-le-Willows. Born in 1857, he experienced the extreme loss that many of his generation did through the deaths of some of his children.

In 1881 he married Eliza Cook who was hearing. Eliza already had a son and the couple had 8 more children together. One died as a baby and another aged 10. During the First World War, all four of John and Eliza’s sons were of military age, and at least three of them undertook military service. Wilfred Walter, born in 1886, served in the Suffolk Regiment. He married in Ipswich in 1916, and was killed in France in January 1918, the third child that John and Eliza lost.

In 1898 a Mission to the Deaf and Dumb in Norfolk and Suffolk was established by the Bishop of Thetford. This was initially part of the Church of England, and aimed to provide access to Church services, education, training, employment assistance, and social opportunities for deaf people. This was established by hearing people, with only occasional deaf employees.

One such employee was George English, who was born deaf in East Ham, Essex, in 1907. He was Missioner for Bury St Edmunds in the late 1940s and early 1950s. His job would have included getting to know local deaf people and supporting their employment and wellbeing. In October 1949 he conducted a harvest festival thanksgiving service for local deaf people at St John’s Church in Bury St Edmunds. He must have maintained relationships with the area as in 1962 he took part in a service in the Abbey Gardens.

He went on to have a long career supporting deaf people and teaching sign language and as a lay preacher in the Church of England.

George English, pictured in the Worthing Herald, 5th June 1981.

During the twentieth century the Mission split up into more local deaf associations. In 1997, as the Bury St Edmunds Deaf Association marked 100 years since the old Mission was founded, it was clear that attitudes had shifted, with the organization working ‘with deaf people, instead of for them’.

Saving these stories

All of this historical research helped to inform the films we made for Deaf Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future which you can watch on The Offshoot Foundation YouTube channel .

The database and background research will be deposited with Suffolk Archives , where it will be available for researchers in the future.

In the meantime, if you would like to search the database we have created, please contact us at

info@theoffshootfoundation.com

Postscript by

Stephen Iliffe,

Stephen Iliffe,

deaf photographer, writer and advocate

For the 21st century deaf community to put into perspective its present and future, it helps to first understand its past.

If we go back 200 years, we find that the UK’s largest deaf communities emerged in Britain’s industrialised cities. The residential deaf schools acted as a magnet – drawing in deaf people from the towns and villages of the surrounding counties. And when ex-pupils remained in the cities, they formed active societies with busy social calendars and regular journals. And this is this where the majority of our present understanding of ‘deaf history’ resides.

In the less-industrialised and coastal counties, like Suffolk, deaf people were more geographically-dispersed, less well-networked, often lacking the obvious focal point of a residential school, and so inevitably less well-documented by historians.

This is what makes the Deaf Perspectives project such an exciting and valuable resource. From the bare bones of census data, school rolls, and newspaper reports we can now begin to see the outline of a ‘Suffolk deaf community’ – such as it was – emerging from historical obscurity.

And, we get clarity on crucial questions, such as how did generations of Suffolk deaf children in Victorian times even get an education in a county that even today has never had its own residential deaf school. Answer: they were often sent to deaf schools in neighbouring counties – Margate, Great Yarmouth, or further still to London, Manchester, Birmingham.

Those who lived and worked in Suffolk included some outstanding personalities – like Walton Burrell and George English – long-forgotten names whose stories were lost to obscurity until Deaf Perspectives bought them back to life. How we can marvel at their resourcefulness – Walton, an enterprising photographer who travelled also overseas to Japan, Hawaii, Australia and many other places. How they thrived in a county where modern concepts such as ‘deaf rights’, ‘equal opportunities’ and ‘access’ were still unheard of.

We also see in Deaf Perspectives, the outline of how deaf people fared before the post-War welfare state was founded in 1946. Contrary to popular myths and stereotypes, ‘deaf and dumb’ people (as they were labelled at the time) mostly did make a productive contribution to society – albeit almost exclusively in manual trades – tailoring, carpentry, etc. And not forgetting those who stayed at home, women in particular, were unpaid housemakers, parents, volunteers, pillars of the community too.

But we also see how some deaf people fell through the safety net and into the grim workhouses or the criminal justice system – often for no reason than the inability of hearing people and institutions around them to empathise, communicate and provide support. At this time, the general public would have casually accepted this as the inevitable fate of people who couldn’t hear. Today, we can frame it as ‘prejudice’, ‘institutional failure’ and ‘discrimination’.

If these historical findings were to merely languish on a shelf, Deaf Perspectives would have failed. But by turning it in a vibrant educational online resource, informed, led and presented by local deaf students, the project has become a springboard for future action.

In many ways, Deaf Perspectives is a vital starting point – for urgent conversations about deaf people’s past, present and future. A stimulus for further work to flesh out Suffolk’s deaf history and bring it to glorious life and to inspire future generations too.

Deaf Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future is made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund. Thanks to National Lottery players, we have been able to provide opportunities for young people to develop new skills and share their perspective on the world.